The Tainted Beauty of The Pernkopf Anatomy Atlas

Have you ever looked at an anatomy textbook and asked yourself where the specimens for the illustrations originated? We'd like to think that the specimens came from willing donors wanting to give their bodies to science in order to educate future generations. Unfortunately this is not always the case, as best exemplified in the controversial origin of the specimens in Eduard Pernkop's infamous Topographische Anatomie des Menschen (Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy). His atlas has been hailed as one of the most important anatomical atlases since the work of Vesalius, a very prestigious statement. But, speculation and indirect evidence have led to the conclusion that Pernkopf used the murdered bodies of men, women, and children from the Holocaust for his atlas of anatomy.

Who was Pernkopf?

Eduard Pernkopf was born in Austria in 1888. His father died in 1903 and in order to support his family he decided to go to medical school. After receiving a medical degree in 1912 from the Vienna Medical School, Pernkopf taught anatomy here and there for the next 14 years throughout Austria. He came back and became professor of anatomy and eventually rose to director of the Anatomical Institute at the University of Vienna.

While Pernkopf was a successful anatomist, he was also a fervent believer in National Socialism. He joined the Nazi party in 1933. Soon after Hitler invaded Austria in 1938, Pernkopf was chosen as Dean of the Vienna Medical School. His first assignment included purging the medical school faculty of all Jews and undesirables. This "purging" resulted in the loss of 153 of the 197 faculty members, including 3 Nobel Laureates.

In his first official speech to his selected faculty members, he laid down his beliefs,

“To assume the medical care — with all your professional skill — of the body of the people which has been entrusted to you, not only in the positive sense of furthering the propagation of the fit, but also in the negative sense of eliminating the unfit and defective. The methods by which racial hygiene proceeds are well known to you: control of marriage, propagation of the genetically fit whose genetic, biologic constitution promises healthy descendants: discouragement of breeding by individuals who do not belong together properly, whose races clash: finally, the exclusion of the genetically inferior from future generations by sterilization and other means.”

The Pernkopf Atlas

As a professor of anatomy, Pernkopf wrote a detailed dissection manual for his students. The manual grew after years of teaching and attracted the attention of the publisher Urban & Schwarzenberg, then a big publisher of anatomy texts. Pernkopf eventually signed a contract for the production of a multi-volume Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy.

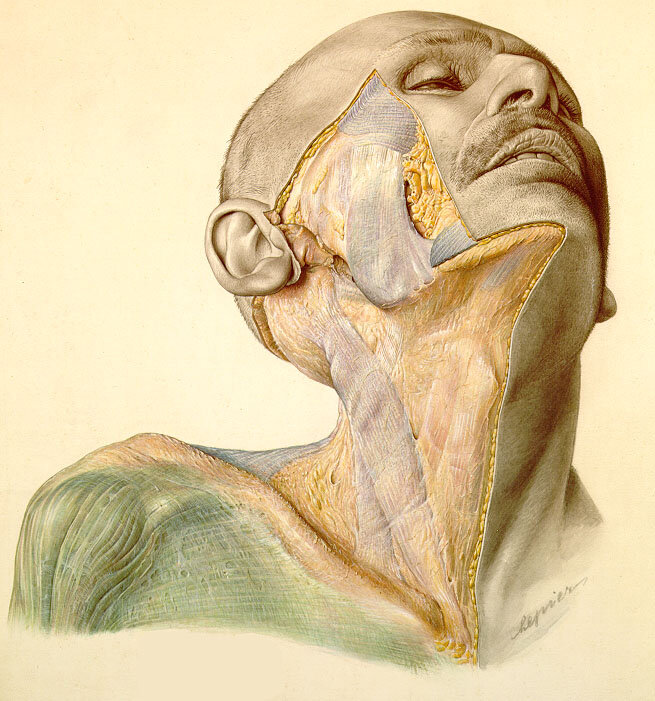

Pernkopf completed the first atlas, Topographische Anatomie des Menschen, in 1943. It took a team of talented Viennese artists three decades to complete the more than 800 exquisite watercolor paintings in the atlas. The distinguished artists included Erich Lepier, Ludwig Schrott, Karl Endtresser, and Franz Batke. Pernkopf was very strict in ensuring that the artists make the paintings of the dissections look like living tissue, thus resulting in some of the most beautifully colored anatomical illustrations ever created at that time. It is said that even reproductions cannot do justice to the colors of the original illustrations.

Pernkopf meticulously wrote the detailed text that accompanied the illustrations.

"A "workaholic," he was obsessed with the atlas for the rest of his professional life. Rising at five a.m. to work on the text, he wrote notes in shorthand for his wife, Ruth, to transcribe and type during the day while he was at the university. There, in addition to his teaching and official duties, he oversaw the preparation of the dissections by his assistants and graduate students in the institute."

Pernkopf died from a sudden stroke in 1955 before completing the fourth edition of his atlas.

Tainted origins of the Pernkopf Atlas

Like Pernkopf, the artists for his atlas were also active Nazi party members. Erich Lepier even signed his paintings with a Swastika, which up until 15 years ago remained in editions of the atlas, but have been airbrushed out since then.

Karl Endtresser, academic painter; Ludwig Schrott, Jr.; Univ. Prof. Dr. med. Eduard Pernkopf; Wener Platzer; Franz Batke, academic painter. Vienna, March, 1952

In 1995, an article in the Annals of Internal Medicine, summarized the history of the University of Vienna in 1938. They found that the Anatomy Institute of the University of Vienna, where Pernkopf worked, received the cadavers of prisoners executed during the Holocaust. The University of Vienna conducted their own investigation and found that in fact 1377 bodies of murdered victims, including children, were taken into the Anatomy Institute. It is also known that Pernkopf willingly accepted the bodies of murdered adults and children to the Institute. Therefore, it is almost without a doubt that Pernkopf used these bodies for the dissections from which the anatomical illustrations were drawn.

It is obvious that the bodies of the victims were used without permission from the victims themselves or their families. It is these unethical origins that taint Pernkopf's Atlas. There is no direct evidence that the bodies used came from victims of the Nazi Holocaust, however there are certain details in the illustrations that have raised suspicions. For example, one illustration clearly shows the wasted appearance and crudely shaven head of a young man. Cadavers generally have cleanly shaven heads. Another illustration of a dissection of the femoral region of a male shows that he was circumcised.

Whether the bodies were victims of the Holocaust or not, the author and artists of the atlas were highly involved Nazi party members not ashamed to show their commitment. That alone taints the atlas. Pernkopf was never charged with war crimes, but he did spend 3 years in an Allied prison camp near Salzburg after the war. It is said that his life was never the same afterwards, although he still continued to work on his atlas up until his death.

As of August 1997, the University of Vienna has provided all libraries carrying the Pernkopf Atlas with an insert titled, "Information for Users of Pernkopf's Atlas." The insert provides the political background of Pernkopf along with the statement,

"Currently, it cannot be excluded that certain preparations used for the illustrations in this atlas were obtained from (political) victims of the National Socialist regime. Furthermore, it is unclear whether cadavers were at that time supplied to the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Vienna not only from the Vienna district court but also from concentration camps. Pending the results of the investigation, it is therefore within the individual user's ethical responsibility to decide whether and in which way he wishes to use this book."

The final report of the commission at the University of Vienna was issued October 1, 1998. The investigation revealed that the Institute of Anatomy received at least

"1,377 bodies of executed persons, including 8 victims of Jewish origin. On the basis of a general decree of February 18th, 1939, the bodies of persons executed were assigned to the Department of Anatomy of the nearest university for the purposes of research and teaching. No proof could be found that bodies had been brought to the Vienna Department of Anatomy from the Mauthausen camp complex. The presumption and suspicions that some of the illustrations might be of prisoners of war or Jewish victims are based predominantly on impressions which strike the critical observer. In these cases, however, the investigation was able neither to prove nor to disprove the suspicions. Because of the systematic practice of making specimens anonymous, it seems likely that a final clarification of such suspicions will not now be possible."

Conclusion

Medical history is spotted with ethical controversies surrounding the origin of cadavers for medical education. Even today the origins of the bodies used in the famous Body Worlds exhibits have come under scrutiny. But the Pernkopf Atlas provides the pinnacle of debate over the ethical use of human remains for medical education. Opinions of the atlas range from praise to rejection. Since investigations into the University of Vienna began, efforts have been made to ban the book from medical libraries.

At the same time, the Pernkopf Atlas is a very high-quality, extremely detailed anatomy text of value to any student studying anatomy, and those attributes cannot be removed. The atlas has been hailed as an "outstanding book of great value to anatomists and surgeons" by the New England Journal of Medicine, and "classic among atlases with illustrations that are truly works of art" by JAMA. The tainted nature of the atlas makes it difficult to fully appreciate its beauty and importance to the medical field, and the artists can never be completely praised for their painstaking work. Either way it will always remain controversial and elicit deep response from whoever encounters Pernkopf's Atlas.

Sources

Williams DJ. The history of Eduard Pernkopf's Topographische Anatomie des Menschen. J Biocommun. 1988. Spring; 15:(0):2

Atlas, M.C. Ethics and access to teaching materials in the medical library: the case of the Pernkopf atlas. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000. January; 89(1): 51-58.