Introducing the Father of Modern Medical Illustration

When I tell any sort of medical professional that I'm going to be a medical illustrator they immediately respond "Oh, like Netter?" Frank Netter may be the most well known medical illustrator, but it was the German artist, Max Brodel (1870-1941), who established the profession in America and is considered to be the father of modern medical illustration.Brodel received his formal art training at the Leipzig Academy of Fine Arts in Germany. In 1888, after graduating, he began creating anatomical and scientific illustrations for Dr. Carl Ludwig, the Director of the Institute of Physiology at the University of Leipzig. Brodel quickly learned that medical illustration was not easy without having a background in science or medicine.

When I tell any sort of medical professional that I'm going to be a medical illustrator they immediately respond "Oh, like Netter?" Frank Netter may be the most well known medical illustrator, but it was the German artist, Max Brodel (1870-1941), who established the profession in America and is considered to be the father of modern medical illustration.Brodel received his formal art training at the Leipzig Academy of Fine Arts in Germany. In 1888, after graduating, he began creating anatomical and scientific illustrations for Dr. Carl Ludwig, the Director of the Institute of Physiology at the University of Leipzig. Brodel quickly learned that medical illustration was not easy without having a background in science or medicine.

I did not know then that the only way to plan a picture is to leave paper and pencil alone until the mind has grasped the meaning of the object. Copying a medical object is not medical illustrating. The camera copies as well, and often better, than the eye and hand, in medical drawing full comprehension must precede execution.1

Through Dr. Ludwig, Brodel met Dr. Franklin P. Mall, an anatomist and future head of the anatomy department at the Johns Hopkins Medical School. Mall saw the talent and potential in the young Brodel and persuaded him to move to Baltimore, Maryland in 1894 to become an illustrator for the Johns Hopkins Medical School. Working directly in the medical field, Max had no choice but to immerse himself in medicine. When he was not illustrating he spent most of his time reading medical texts, observing surgeries and dissecting cadavers. Here's an interesting snippet on Max's adventures in dissecting.

Working directly in the medical field, Max had no choice but to immerse himself in medicine. When he was not illustrating he spent most of his time reading medical texts, observing surgeries and dissecting cadavers. Here's an interesting snippet on Max's adventures in dissecting.

Brodel dissected human bodies without using gloves so he could fully understand his subjects. Brodel developed a streptococcus infection on the ulnar side of his left hand (fortunately not his dominant right hand) after mistakenly cutting himself while dissecting an infected cadaver. After four surgeries by the great neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing (1869-1939), and some recovery time, Brodel's hand improved. Cushing studied surgery under the guidance of the father of American surgery, William Steward Halsted (1852-1922), at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. During recovery, Brodel was fascinated by the loss of sensation in his hand and took to studying ulnar nerve injury. With a pair of forceps, he applied light pressure to different areas on his hands to map out the areas of sensation loss due to ulnar nerve damage. After several drawings on "progress note" paper that physicians use to make notes on patients, Brodel drew the regions of the hand that are supplied by the ulnar nerve. A century later, we can still learn from Brodel's misfortune.1

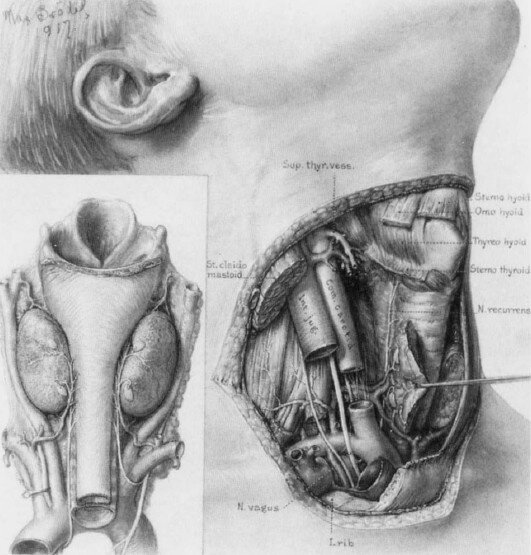

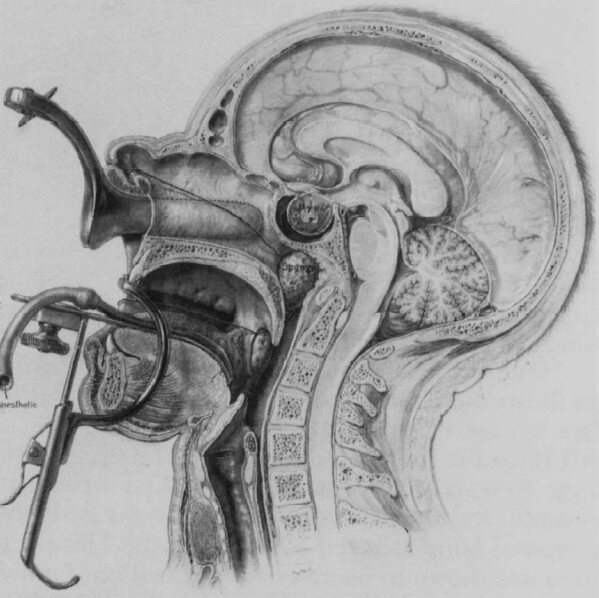

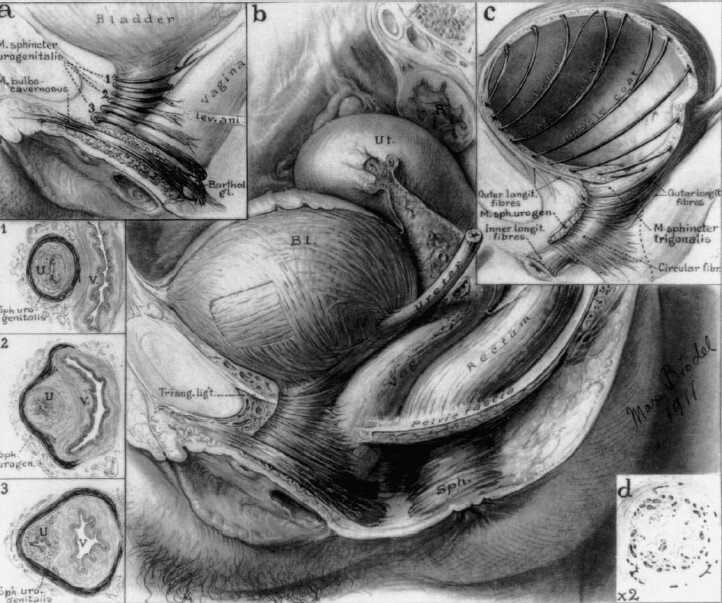

Word of Brodel's talent and the importance of medical illustration spread across the United States. Soon he received many offers to work at other universities. In 1911, in an effort to keep Brodel at Johns Hopkins, a new department was established called the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine. Brodel was asked to become the head. The purpose of the department was to formally train medical illustrators and establish medical illustration as a profession. Brodel worked hard to find a balance between medical knowledge and artistic skill, something that every medical illustrator to this day is trained to accomplish. Brodel went on to train many medical illustrators over the next 30 years, many of whom went on to establish medical illustration programs at other universities. One such student, Tom Jones, went on to establish the second medical illustration program in the country at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1921. Jones later went on to establish the Association of Medical Illustrators (AMI) in 1945.  Brodel devised the method of using carbon dust to create a two tone technique that could capture the sparkling highlights that characterize wet, living tissue. Carbon dust involves using special paper coated with white layers of chalk or clay. Carbon dust is then layered on the paper in stages to create shadow and depth. The results are incredibly rich tonal images that capture form well. Erasers can then be used to lift out bright highlights and create great contrast. 1Read the excellent essay written on Brodel by Pia Pace-Asciak, B.A., H.B.Sc., M.A.Sc. at the University of Ottawa's website.

Brodel devised the method of using carbon dust to create a two tone technique that could capture the sparkling highlights that characterize wet, living tissue. Carbon dust involves using special paper coated with white layers of chalk or clay. Carbon dust is then layered on the paper in stages to create shadow and depth. The results are incredibly rich tonal images that capture form well. Erasers can then be used to lift out bright highlights and create great contrast. 1Read the excellent essay written on Brodel by Pia Pace-Asciak, B.A., H.B.Sc., M.A.Sc. at the University of Ottawa's website.